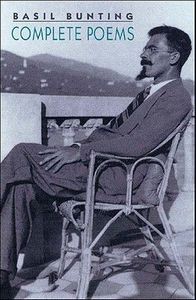

At last in print, the complete poems of the great Northumbrian poet-admired by Pound, Yeats, and Zukofsky-containing his masterwork "Briggflatts."

A master of song poems which celebrate-and incarnate-the music of nature and history, love and mythology, religion and language, Basil Bunting (1900-1985) was a major figure in Modernist poetry, recognized by Pound and Zukofsky as early as the 1930s, and crowned, with the 1966 publication of his masterpiece "Briggflatts", Britain's greatest poet. The poet himself called his great epic poem "old wives' chatter, cottage wisdom," but for many writers "Briggflatts" is one of the dozen great poems of the 20th century: as Cyril Connolly put it, "the finest long poem to have been published in England since T.S.Eliot's Four Quartets."

As well as "Briggflatts" (long out of print in the US, and now only available in our edition), this new Complete Poems includes Bunting's other great sonatas, most notably Villon (1925) and The Spoils (1951), along with his two books of Odes, his vividly realized "Overdrafts" (as he called his free translations of Horace, Rudaki, and others), and his brilliantly condensed Japanese adaptation, Chomei at Toyama (1932). It also includes his posthumous Uncollected Poems. This centenary edition has an introduction by Richard Caddel, Director of the Basil Bunting Poetry Center at Durham University.

During World War II, Bunting served in British Military Intelligence in Persia. After the war, he continued to serve on the British Embassy staff in Teheran until he was expelled by Muhammad Mussadegh in 1952.

With the outbreak of World War II, a radical change occurred in Bunting's life. Raised as a Quaker, Bunting had been a conscientious objector to the First World War and had even been imprisoned for a time. But the forty-year-old poet had a far different response to the Second World War: he enlisted in the British Royal Air Force (RAF). Keith Alldritt has argued that Bunting's willingness to serve was predicated as much on his need for a job as it was on his anti-fascist sentiments (Spy 97). In any case, Bunting went rapidly from an underemployed sailor in Los Angeles to various positions with the RAF, including work on a reconnaissance balloon off the Scottish coast, several stints as a truck driver, a position as an interpreter in Iran, and a prestigious post as an intelligence officer in Italy (Alldritt, Spy 97-106). The extent to which this military service affected Bunting's thinking about aesthetics is apparent in a humorous yet unsettling letter he wrote to Louis Zukofsky during the war. "What do 'I feel with a machine-gun?'," Bunting wrote. "Well it depends on the gun" (qtd. in Alldritt, Spy 98):

I criticize a machine by nearly the same criteria as I do a work of art. A Lee-Enfield rifle, a Hotchkiss machine gun, have nothing superfluous nor fussy about them. They are utterly simple - having reached that simplicity via complication and sophistication galore. The kind of people who, if they had literary minds at all, would like euphemism or trickiness, prefer Lewis guns or Remington or Ross rifles. My machine-gun is a Hotchkiss and I feel toward it something similar in kind to what I feel for Egyptian sculpture . I think Holbein or Bach or Praxiteles, as well as Alexander, would have appreciated a Hotchkiss gun" (qtd. in Alldritt, Spy 98).

Alldritt sees in this passage a unification of "the practical and the aesthetic" (Spy 98). But there is more than practicality involved with this assessment of modern weaponry. Bunting's joking praise for the Hotchkiss machine gun recalls Walter Benjamin's criticism of those who conflate aesthetics with nationalist politics: "All efforts to render politics aesthetic culminate in one thing: war.. Only war makes it possible to mobilize all of today's technical resources while maintaining the property system" (241). To make aesthetic judgments on the "technical resources" of modern warfare normalizes the fact of war itself. Thus, Bunting's treatment of his gun involves a rather bitter irony.